It Really Did Save Both of Us

I recently retired after many years from Family Voices, a national advocacy organization for families with children with special health care needs. Unlike many of the Family Voices staff, I don’t have kids or grandkids with special health care needs. I learned so much from the families I worked with, and got windows into what life can be like with a child with serious medical complexities. I was recently reminded of my one experience in that world when the news reported the appearance of a “mysterious” childhood illness that seemed to be somehow related to the Coronavirus, and somewhat similar to a previously identified illness, Kawasaki’s Disease. My son had Kawasaki’s years ago, and therein lies a tale.

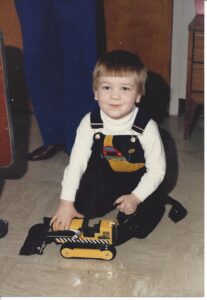

It was 1985, and we were still living in the Atlanta area. Dan had just turned two years old late that February, and had his first ear infection. As was typical for the day, that meant a round of antibiotics, followed by a pediatrician recheck two weeks later.

The Saturday night before that recheck, Dan started throwing up. He wasn’t able to keep anything down, but he was still nursing, and I hoped he’d get enough of that easily-digestible milk to sustain him. By Sunday he was crying blood-stained tears. Unnerved and unsettled, we figured something more than a simple tummy upset was going on.

Our recheck appointment was set for the next morning. The pediatric practice we used had four doctors, and the one we happened to be seeing for this ear infection had worked in Hawaii a few years before—experience that would factor into how this episode unfolded.

“I’m not sure, but I think this might be Kawasaki’s Syndrome,” the doctor told us. She explained that this was a relatively new disease first identified in Japan, and one that she’d seen in Hawaii. It affects the skin, lymph glands, and mucous membranes—hence the bloody tears. In some cases it affects the heart, and some of those could be fatal. OH MY. She asked us to come back the next day.

Dan continued to throw up, and we spent the night in the living room—him sleeping (sort of) on the couch, and me not sleeping (mostly) on the floor beside him. The next morning, we packed for the hospital, and headed back to the pediatrician’s office. By this time, Dan was dehydrated, and the doctor was more convinced that he might have Kawasaki’s, and sent us to Scottish Rite Children’s Hospital in Atlanta.

Scottish Rite was set up for the realities of handling sick children—all rooms are private, with chair/recliners for a parent to stay close by, understanding that some things are just as important as medicine in caring for a sick child. They gave him an IV and started pumping fluids. Thankfully, they were happy that he was still nursing, and encouraged me to nurse him any time he wanted. That was the only thing that was keeping either of us calm (sort of).

For those who have never nursed a baby, let alone a toddler, it may be hard to understand that its value goes way beyond a food delivery system. By two years of age, nursing is less about the food (milk), though that is still good stuff, and more about the connection. In this instance, this was the one thing that I could do for Dan that nobody else could, and the one thing that provided any sense of normalcy. And, that helped both of us cope through what was a progressively more scary situation.

By Thursday, Dan’s heart had swollen and was racing. It sounded like the theme from the Lone Ranger—da da dum, da da dum, da da dum: congestive heart failure. Definitely NOT what we wanted to hear, as we were then in that smaller group of cases with heart involvement. They moved him to ICU, but still allowed me to come in anytime (after scrubbing up and donning a gown) and nurse him if he wanted. We started out in a general ICU waiting room with other parents, but whereas I’d been able to hold it together up until that time, I was losing it. The hospital chaplain offered to let us wait in his office, and we camped out there for the night.

Every so often I’d go through the scrubbing routine to get in and offer a little comfort for both of us. It was a long scary night, but he was holding his own. The next morning, our regular pediatrician was back on duty. She looked at Dan’s chart and noticed that they’d never cut back his IV fluids, and that, plus all the milk he was getting from me through comfort nursing, was making his heart swell. A child without Kawasaki’s who got that much fluid would just pee it off, but for whatever reason, it was going straight to Dan’s heart. She took him off the IV fluids (but still let me continue to nurse him), and by the end of the day, he was back out of the ICU. We brought him home on Saturday, and were told that the clincher for the Kawasaki’s diagnosis was that in another week or so the palms of his hands and the soles of his feet would start peeling off in large sheets. And they did, right on schedule.

Because some of these kids with heart involvement risked the potential for developing a coronary artery aneurism, Dan had various echocardiograms (heart ultrasounds), starting in the hospital and beyond. A year after the initial infection, we got a letter from his cardiologist saying that because they hadn’t known about Kawasaki’s disease long enough to do any long-term tracking of the kids, he was doing “routine” (to him!) mini-heart catheterizations on all his patients. We agonized over it, and ultimately asked the pediatrician for her input. We ultimately decided that the risk from an undetected aneurism was greater than the risk of the procedure. Thankfully, other than an allergic reaction to the dye they injected, it came out fine.

He had another echo done when he was 12 or so, and again, nothing. They don’t know what will happen to these kids when they reach middle age and older, and he’s been checked out thoroughly to do the kind of scuba diving he loves.

At the time Dan had Kawasaki’s, nobody knew what caused it. There was one theory that cleaning carpets stirred up “something” that triggered it. (That wasn’t the case for Dan.) His immunologist told us he thought that Kawasaki’s is an autoimmune disease that happens after an initial infection (in Dan’s case, the ear infection). The infection clears up, but the body keeps fighting itself. And it seems to come in waves. In all of 1984, the CDC counted 85 cases around the country. By March of 1985, Dan was the 85th case. I believe they have since identified a virus that causes it.

A few years after his infection when we were first getting online, I used to hang out on the old Prodigy Parenting Bulletin Boards. Every once in a while I’d see a discussion of Kawasaki’s, often about cases that were far more difficult and tragic than Dan’s. And consistently, at least in this particular venue, the kids who were breastfeeding fared the best. I’m just glad I was still nursing him (with support from my husband, family, and friends). It really did save both of us.

© Melissa Clark Vickers 2020

Back to home page.